The burning of Cap-Français, capital of the French colony of Saint-Domingue, began on June 21, 1793 and marked the start of the island’s uprising.

Jean-Baptiste Chapuy (1760 - 1802?), after Pierre Jean Boquet (1751 - 1817)

Haitian Revolution – The Burning of Cap Français

1794 Etching, 52.2 x 73.6 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.98

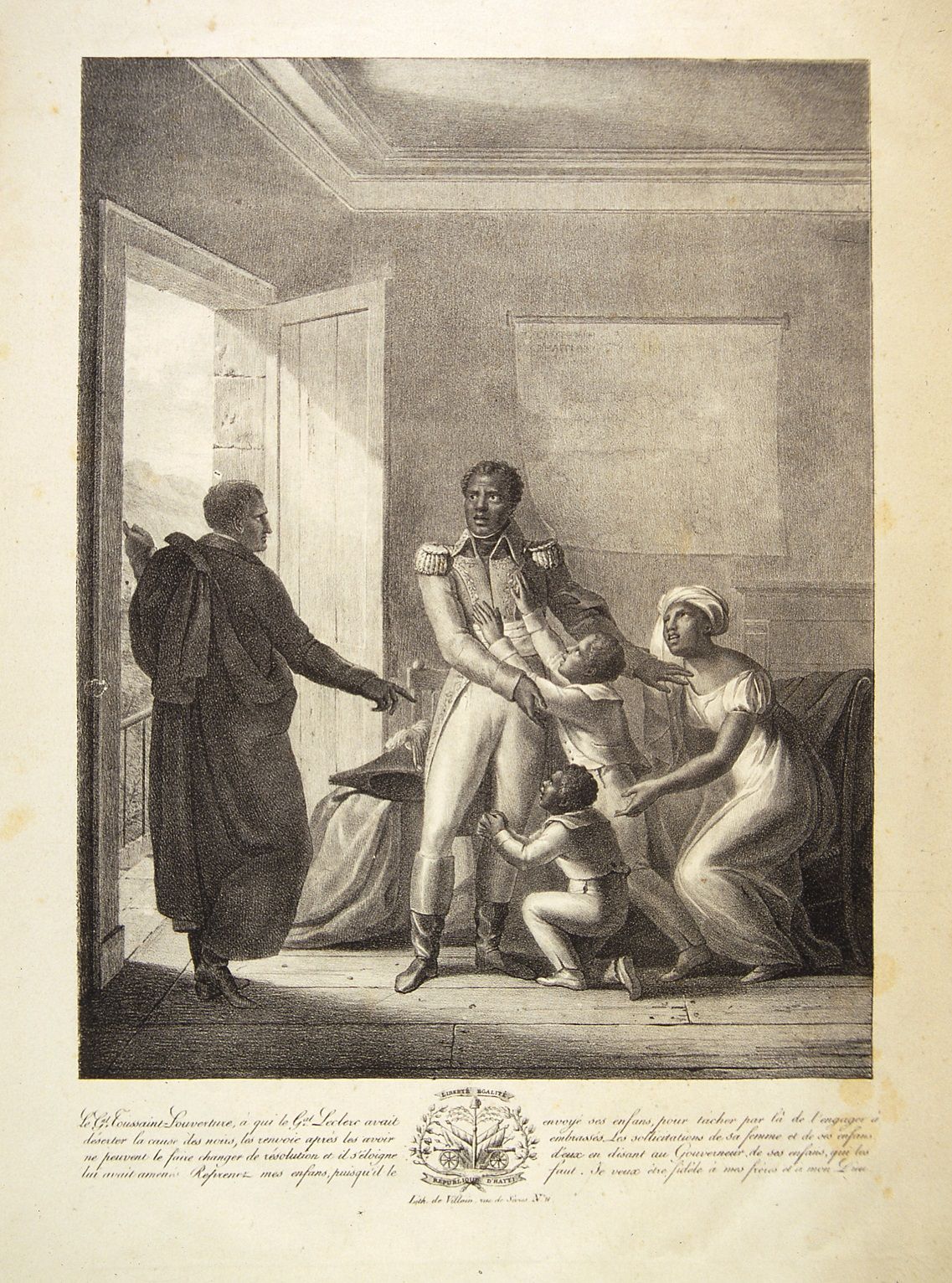

Toussaint Louverture was born in Saint-Domingue in 1743. Legally freed in around 1776, he took part in the slave revolt of 1791. After the abolition of slavery in 1794, Louverture went over to the French. As governor-general of Saint-Domingue, he proclaimed its autonomy in 1801 and drew up a constitution in which he sought to be recognized as governor-for-life.

Denis Volozan (1765 - 1820)

Equestrian portrait of Toussaint Louverture on his horse Bel-Argent

c. 1800 Ink wash painting, 47 x 37.7 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.188

In 1802, the 25,000-strong Leclerc expedition was mounted to restore the old order. On June 7, 1802, Toussaint Louverture was captured and deported to France. Under arrest, he was imprisoned at Fort de Joux in the Doubs region, where he died on April 7, 1803. His wife Suzanne and two sons, Isaac and Placide, were also deported to France. Isaac found asylum in Bordeaux, up until his death in 1854.

Villain

General Toussaint Louverture being begged by his wife and children to abandon the Black cause

1822 Lithograph, 46 x 33.2 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.190

The two sides of this toy for adults present two diametrically opposed visions of a society that was slave-owning at this time: on the obverse, the Slave Trade is inspired by the painting by the Englishman George Morland (1763-1804), Execrable Human Traffic (1788). The artist shows and denounces the violence linked to the deportation of Africans to the West Indies. On the reverse of the toy, a “village festival” illustrates the prosperity and simple pleasures of a carefree European population.

Abolitionist “emigrette” toy France,

late 18th – early 19th century

Ebony wood

Musée Le Secq des Tournelles - RMM. Inv. LS.2001.1.27

Abolitionist “emigrette” toy France,

late 18th – early 19th century

Ebony wood

Musée Le Secq des Tournelles - RMM. Inv. LS.2001.1.27

Although enslaved people suffered from this system, they had always resisted in all the slave societies. This gallery aims to highlight these different strategies of resistance, as well as the active and decisive role played by Afro-descendants in the revolts and struggles leading up to the abolition of slavery.

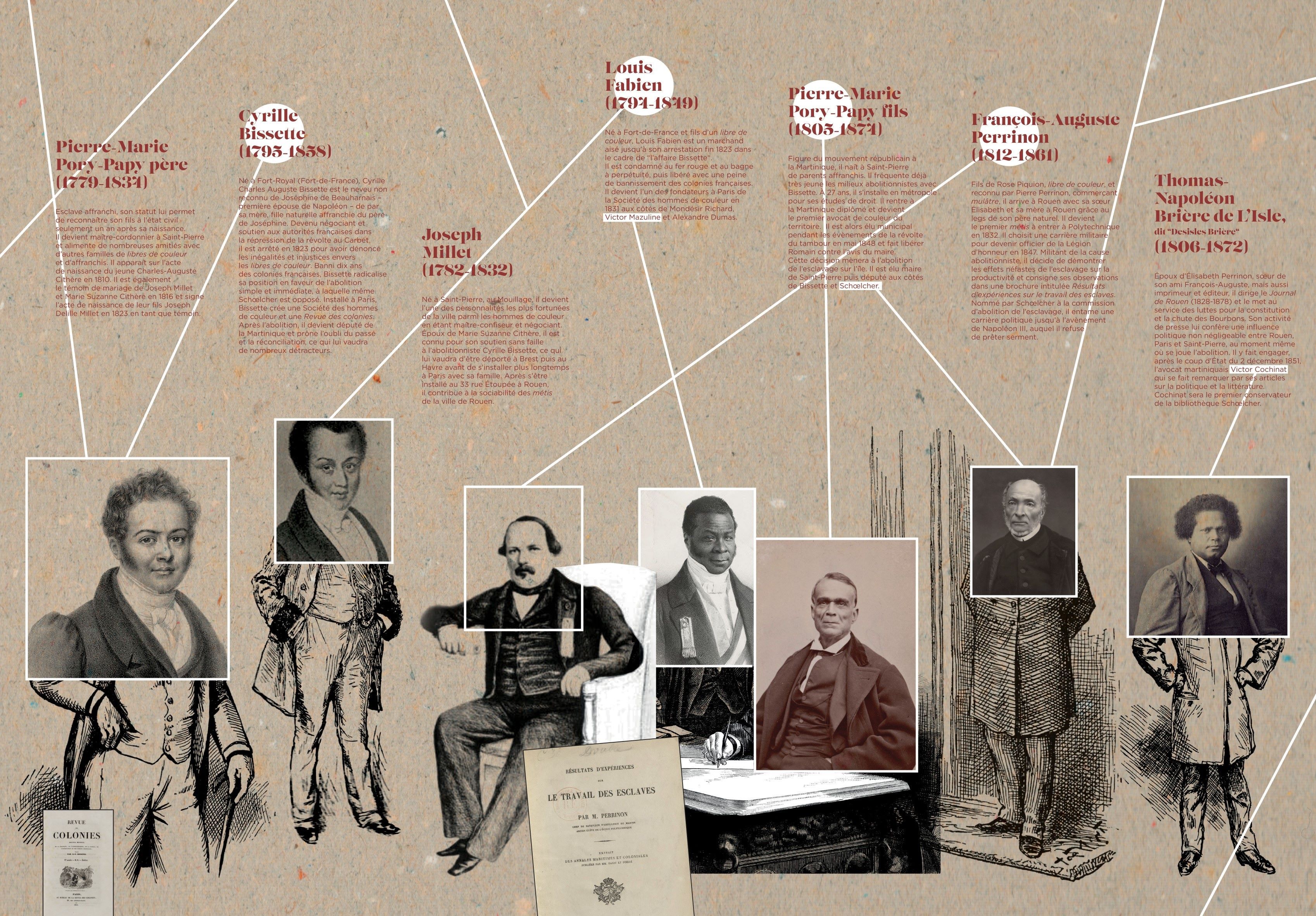

(from left to right)

Pierre-Marie Pory-Papy (1779-1834) father:

As a freed slave, his status enabled him to register his son only one year after his birth.He became a shoemaker in Saint-Pierre (Martinique) and nurtured many friendships with other free-colored families and freed-men. He appears on the birth certificate of young Charles-Auguste Cithère in 1810. He also witnessed Joseph Millet and Marie Suzanne Cithère's wedding in 1816, and signed the birth certificate of their son Joseph Delille Millet in 1823.

Cyrille Bissette (1795-1858):

Born in Fort-Royal (Fort-de-France), Cyrille Charles Auguste Bissette was the unacknowledged nephew of Joséphine de Beauharnais - Napoleon's first wife - through his mother, the freed natural daughter of Joséphine's father. After becoming a merchant and supporting the French authorities in the repression of the Carbet revolt, he was arrested in 1823 for denouncing inequalities and injustices against free-colored people. As he had been banned from the French colonies for ten years, Bissette radicalized his position in favor of simple and immediate abolition, to which even Schœlcher was opposed. Once he had settled in Paris, Bissette created the “Colored men Society” and a “Review from the colonies”. After the abolition, he became deputy for Martinique and advocated forgetting the past and reconciliation, which earned him many detractors.

Joseph Millet (1782-1832):

Born in Mouillage, Saint-Pierre (Martinique), Joseph Millet became one of the city's wealthiest men of color, working as a confectioner and a merchant. Married to Marie Suzanne Cithère, he was known for his unwavering support of abolitionist Cyrille Bissette for which consequently he was deported to Brest and then Le Havre, before moving toParis with his family for a while. After settling at 33 rue Étoupée in Rouen, he contributed to the sociability of Rouen's Métis community.

Louis Fabien (1794-1849):

Son of a free man of colour, born in Fort-de-France to a free man of color, Louis Fabien was a well-to-do merchant until his arrest in late 1823 related to the “Bissette affair”. He was sentenced to red-hot iron and life imprisonment, then released with a sentence of banishment from the French colonies. In 1834, he became one of the founders of the “Coloured-Men Society” in Paris, alongside Mondésir Richard, Victor Mazuline and Alexandre Dumas.

Pierre-Marie Pory-Papy (1805-1874) son:

A key figure in the republican movement in Martinique, he was born in Saint-Pierre of freed parents. From an early age, he frequented abolitionist circles with Bissette. At the age of 27, he moved to metropolitan France to study law. After graduating, he returned to Martinique and became the first lawyer of colour of the country. During the drum revolt of May 1848, he was elected to the town council and had Romain freed against the mayor's advice. This decision led to the abolition of slavery on the island. He was elected mayor of Saint-Pierre, then deputy alongside Bissette and Schœlcher.

François-Auguste Perrinon (1812-1861):

Son of Rose Piquion, a former slave, and recognized by Pierre Perrinon, a mulatto merchant, he arrived in Rouen with his sister Élisabeth and his mother thanks to a bequest from his natural father. He became the first Métis to enter Polytechnique in 1832. He chose a military career, becoming an Officer of the Legion of Honor in 1847. As an activist for the abolitionist cause, he decided to demonstrate the harmful effects of slavery on productivity, and recorded his observations in a brochure entitled Results of experiments about slave labour. Appointed by Schœlcher to the commission for the abolition of slavery, he started on a political career until the advent of Napoléon III, to whom he refused to take the oath.

Thomas-Napoléon Suzanne, known as « Désisles », Brière de L’Isle son (1806-1872):

Married to Élisabeth Perrinon, sister of his friend François-Auguste, but also a printer and publisher, he directed the Journal of Rouen (1828-1878) and used it to support the struggle for the constitution and the fall of the Bourbons. His press activities gave him considerable political influence between Rouen, Paris and Saint-Pierre, just as abolition was looming. After the overturn of December 2, 1851 and the advent of Napoléon III, he hired Victor Cochinat, a lawyer from Martinique, famous for his articles on politics and literature. Cochinat became the first curator of the Schœlcher library.