The backbreaking work in the plantations was the driving force behind many attempts to escape by the slaves, who were then called “maroons”, a term derived from the Spanish cimarrón, which originally referred to the cattle that had escaped from the hills of Santo Domingo. French law is particularly severe with regard to these fugitives or those who protect them. These irons therefore stem as much from the oppression of the settlers as from the strength of resistance and rebellions of the enslaved people that it represses.

Slave shackles

West Africa

19th century

Wrought iron,

Rouen, Natural History Museum - RMM, ss no.

During sea crossings, it was not uncommon for enslaved people who preferred to die of hunger to escape a disastrous (gruesome) fate, to be forced to swallow food using a mouth-opener. Chained together, the survivors thus disembarked in the West Indies with a taste for revolt and mutiny; a recurrent phenomenon from the beginning of colonization due to the massive import of enslaved people into the labor-intensive sugar plantations.

Speculum oris, known as the “mouth-opener”

France, 18th century

Wrought iron, reworked with a file

Rouen, Musée Le Secq des Tournelles - RMM, inv. LS.5761

Dans cet ouvrage dédié au nouveau monde est décrit la géographie de l'Amérique, les territoires et peuples rencontrés, la faune et la flore locales. A la fin de cet ouvrage se trouve un appendice concernant les « marchandises qui se trouvent en Amérique ». Y sont décrits les conditions de vie réservées aux esclaves.

François Dassié,

La Description generale des costes de l'Amerique, havres, isles, caps, golfes, bancs, ecueils, basses, profondeurs, vents & courans d'eau. Des peuples qui les habitent, du temperamment de l'air, de la qualité des terres & du commerce.

Le Havre, Bibl. mun., R 2911.

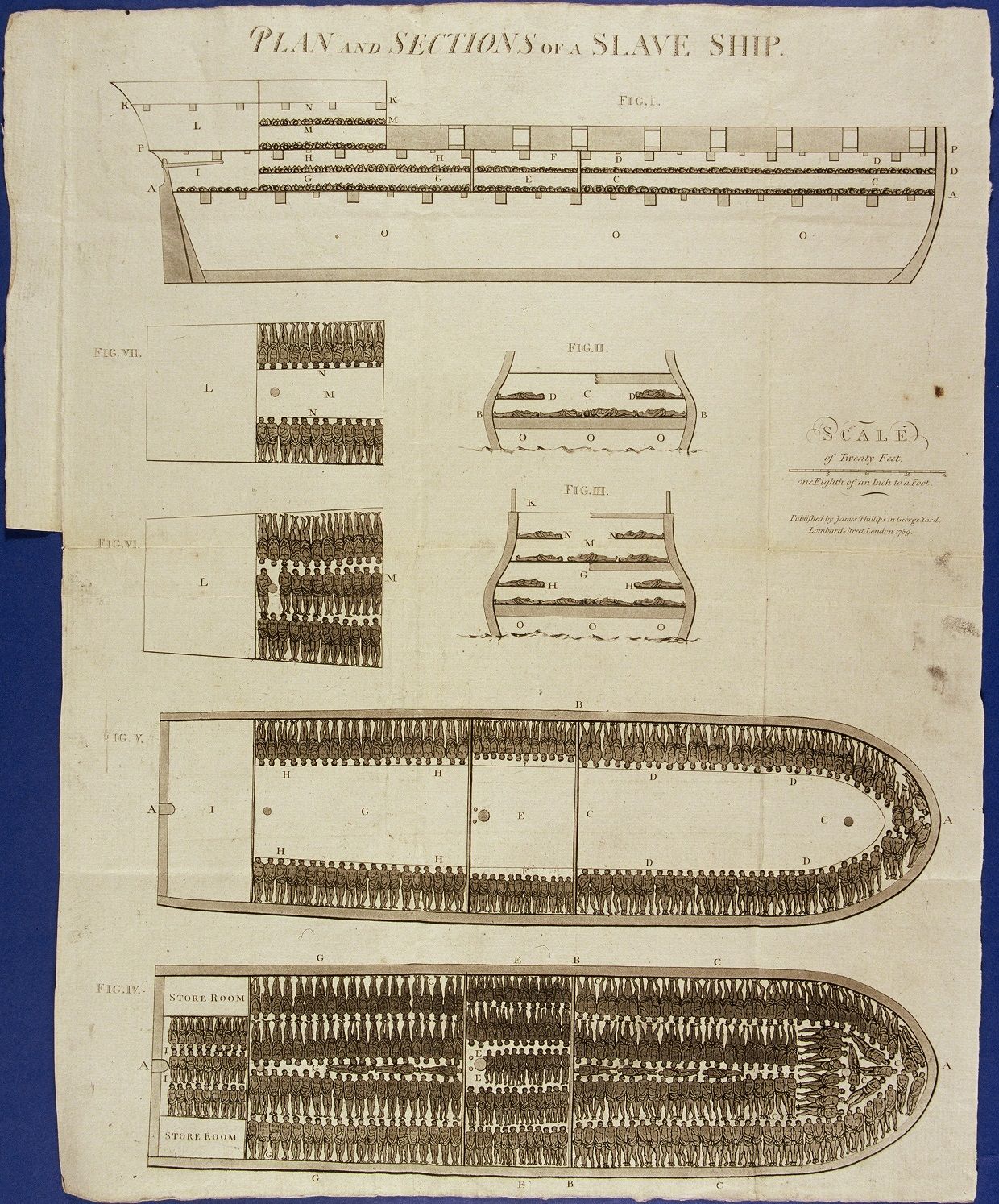

This print from 1789 illustrates the brutal conditions under which African captives were transported on slave ships during Atlantic corssings. The British slave ship the “Brooks” was built in Liverpool in 1781. 454 captives were crammed on board. Men, chained at the ankles in pairs, were stowed from the bow to the center, children at the stern, and women in the midsection. This cross-sectional plan has left a lasting impression.

Plan and Section of a Slave Ship

1789 Print published by James Phillips, London, 49 x 37.4 cm Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.309

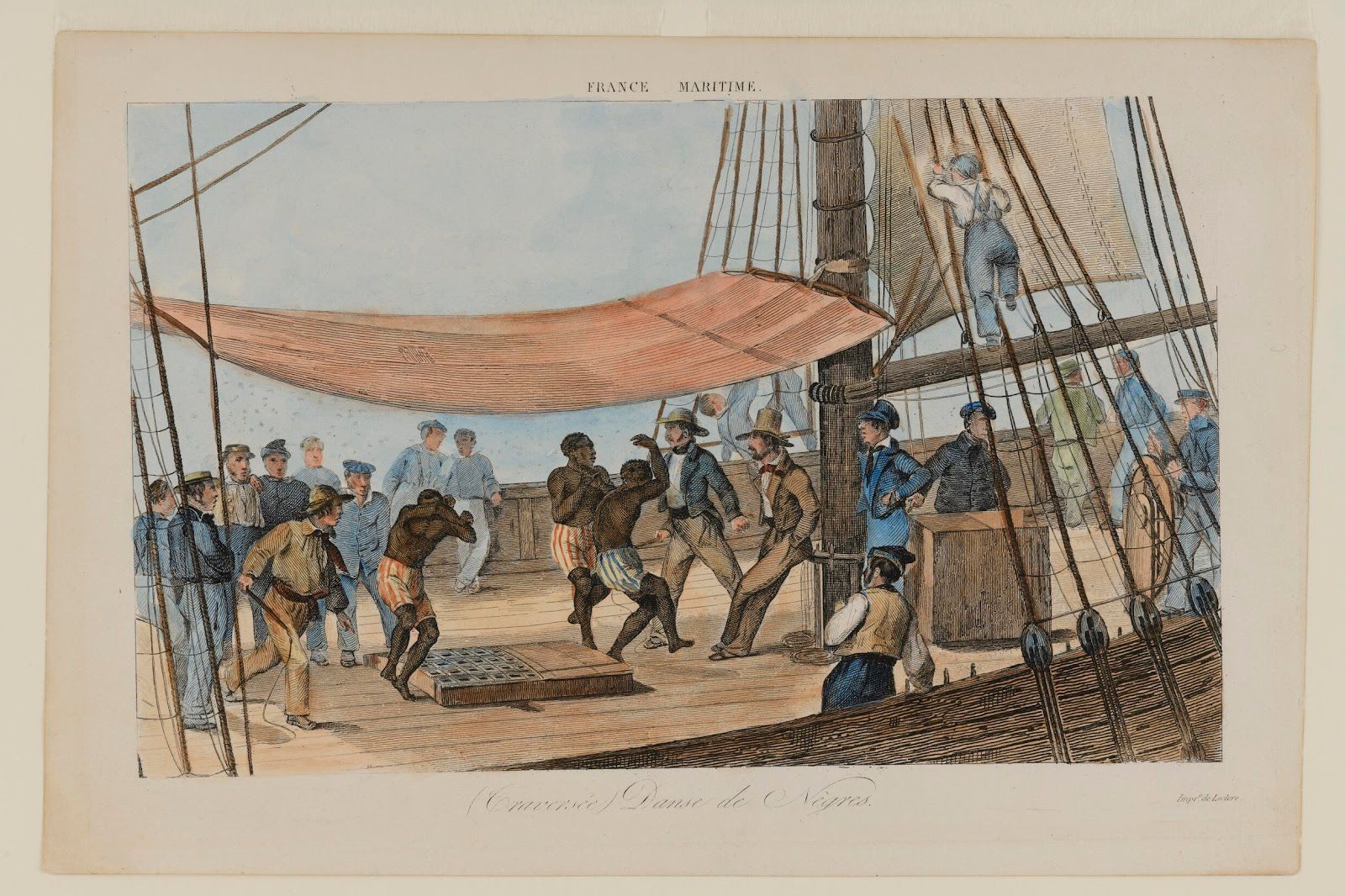

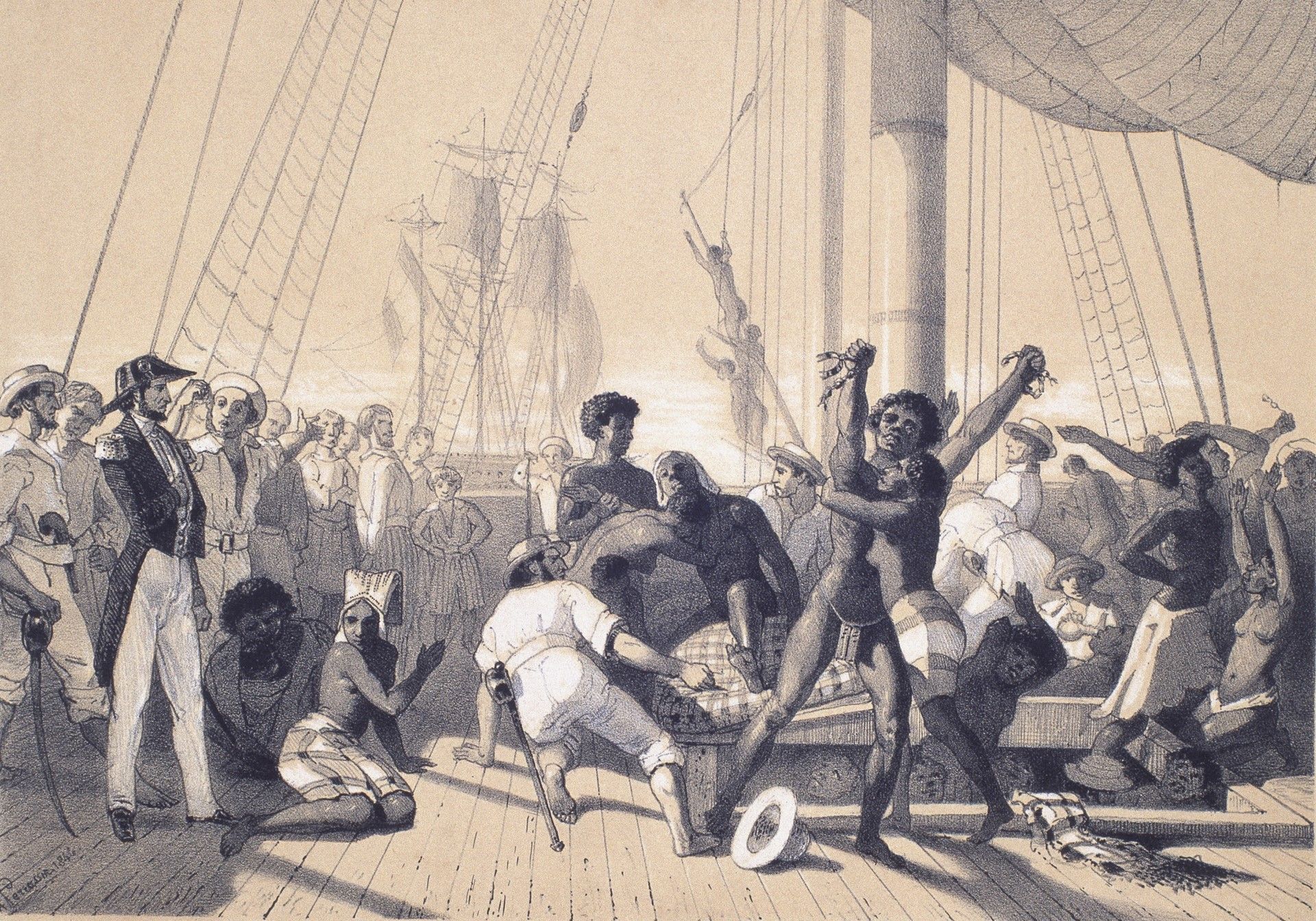

During passages, captives were regularly taken onto the deck in small groups to stretch their limbs and be washed in seawater. They were forced to scrub the deck and dance, often to the rhythm of the whip, while the crew quickly cleaned the hold to combat epidemics. "

Unknown

(Passage) Dance of Negroes

1837 - 1842 Watercolor print from La France Maritime, 18.9 x 26.6 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.315

Anonyme (Traversée) Danse de Nègres 1837-1842 Gravure aquarellée extraite de La France Maritime, 18,9x26,6 cm Bordeaux, musée d’Aquitaine, legs Chatillon, inv. 2003.4.315

Détail de la gravue Danse de nègres 1837-1842 Gravure aquarellée extraite de La France Maritime, 18,9x26,6 cm Bordeaux, musée d’Aquitaine, legs Chatillon, inv. 2003.4.315

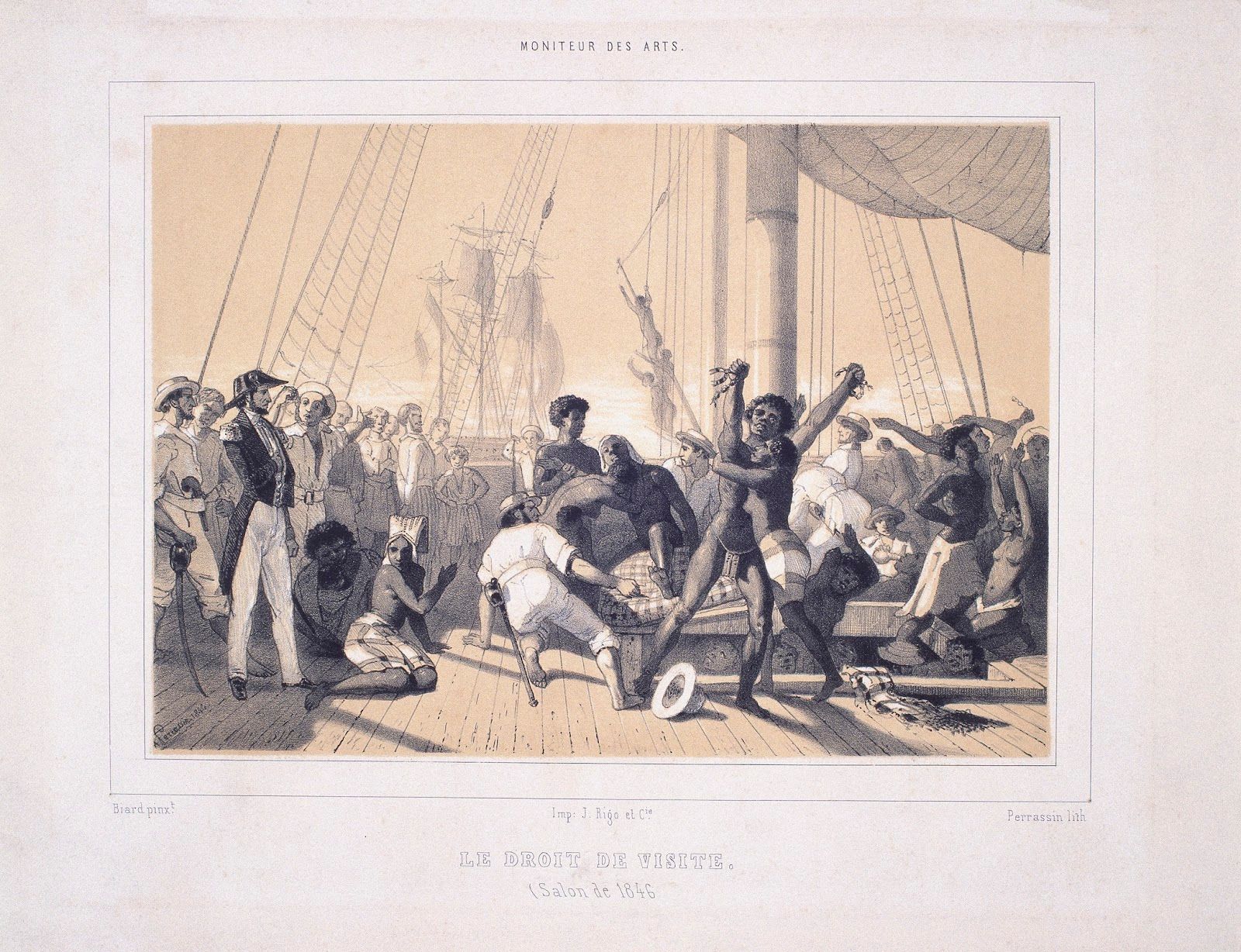

In 1815, the Congress of Vienna marked the first international condemnation of the Atlantic slave trade, in the wake of which the practice was gradually banned by all European states, including France. Despite this, several dozen illegal trading expeditions traveling from Bordeaux were identified between 1815 and 1837. From 1820 onward, French and English naval vessels freed captives aboard clandestine slave ships.

Alexis Perrassin, after François Auguste Biard (1799 - 1882)

Right of access

Post-1846 Lithograph from Moniteur des arts, after a painting (lost) exhibited at the 1846 Paris Exhibition, 23 x 31 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.193

Alexis Perrassin, d’après François Auguste Biard (1799-1882) Le droit de visite Après 1846 Lithographie extraite du Moniteur des arts, d’après un tableau (perdu) présenté au Salon de 1846, 23x31 cm Bordeaux, musée d’Aquitaine, legs Chatillon, inv. 2003.4.193

Détails de la lithographie

Le capitaine Liard aurait commandé le navire la Doris à deux reprises, entre 1802 et 1804. Alors qu'il était en route pour La Réunion, il fit naufrage au large de Zanzibar en janvier 1804 ; il fut sauvé, mais aucun des captifs de sa cargaison ne survécut.

Houllet,

La Doris (en médaillon : le capitaine Liard)

Encre noire et graphite sur papier, 44 X 56 cm

Musée de la Marine, Honfleur, inv. 999.0.470

©David Gadanho

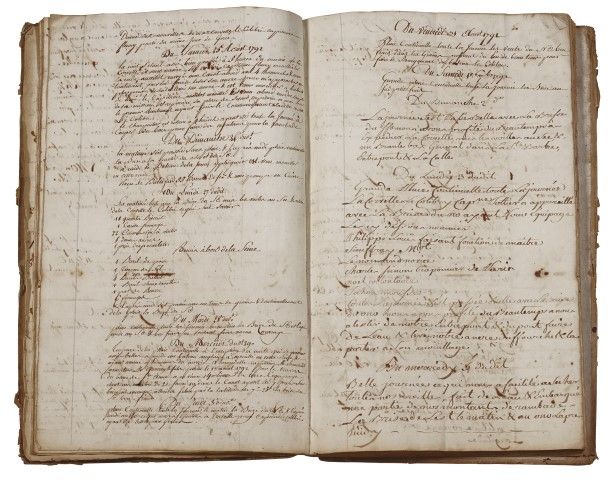

Le capitaine du navire consigne dans son journal de bord à la fois les données météorologiques, les faits notables tels que la rencontre d'autres navires ou encore les modifications de charpente nécessaires à l'entrée en cale des captifs.

Journal de bord du navire l’Aimable Rose pour la côte de Guinée,

Capne Jacque Lacoudrais armateurs Mrs Lacoudrais Père fils aîné & Cie d’Honfleur, 1792-1793,

encre brune sur papier vergé, couverture en velin sur carton fermée par deux lacets,

musée de la Marine, Honfleur, inv.999.0.202

© Illustria

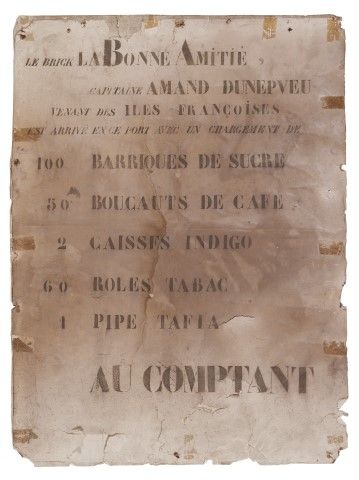

Cette affiche rarissime, probablement placardée sur le port de Honfleur, annonce l'arrivée, en direct des "îles françoises", du navire la Bonne Amitié chargé de denrées coloniales (sucre, café, indigo, tafia).

Affiche annonçant l’arrivée du brick La Bonne Amitié à Honfleur,

craie noire au pochoir sur papier, 61 x 48 cm,

musée de la Marine, Honfleur, inv.VH.2023.0.1

©Illustria

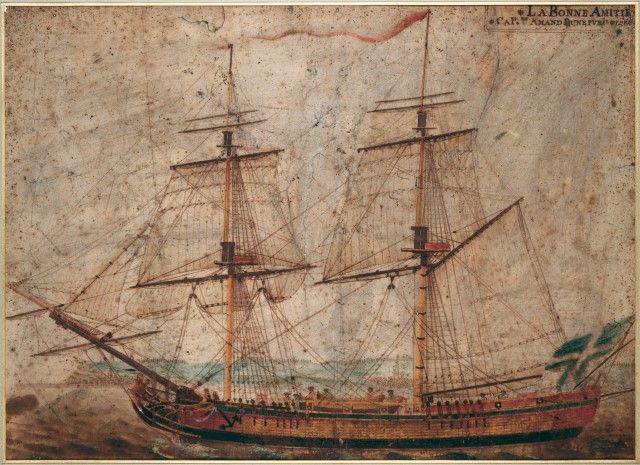

Anonyme

La Bonne amitié, CaP.ne. Amand Dunepveu,

1786

encre, aquarelle et gouache sur papier vergé, 48,2 X 63,7 cm

musée de la Marine, Honfleur, inv.dess.39.134

© Illustria

Le Phénix Capne. Jacque Lacoudrais,

1786,

encre, aquarelle et gouache sur papier vergé, 51,7 X 67,5 cm,

musée de la Marine, inv.dess.39.135, legs Eudes, 1938

©Illustria

Lasting an average of two months, the crossing was an endless ordeal for the men, the women and the children on the ships, who were divided into the “men’s park” and the “women’s park” to prevent any insurrection. They experienced a dreadful nightmare, the anguish was intense, so was the suffering. The crossing is interrupted by “refreshments” on deck to keep the captives in a physical condition in order to resale them in the colonies. Slave ships were spaces of violence, a place of horror and despair.

Notice : © Château des ducs de Bretagne – Musée d’histoire de Nantes

Crossing shackle

18e century

Iron, 7.8 x 60.4 x 21.3 cm

Château des Ducs de Bretagne - Musée d’Histoire de Nantes, INV 965.4.7

Crédit photo : ©François Lauginie / Château des ducs de Bretagne – Musée d’histoire de Nantes