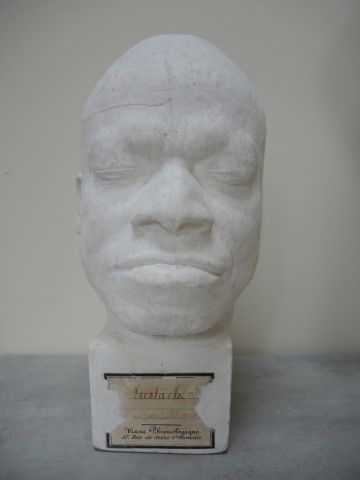

Born into slavery in 1773 in Saint-Domingue, Eustache worked in a sugar factory near Cap-Haïtien, which was the property of Mr. Belin de Villeneuve, the Duke of Mouchy. Belin was a member of the Hôtel de Massiac club, which was a hotbed of anti-abolitionist colonists. Still young at the time of the 1803-1804 revolt, the story goes (according to the speech at the Académie Française’s Prix de Vertu in 1832) that Eustache – also known as the “good negro” – saved his master’s life on several occasions. Due to this, his skull was taken for a model by the phrenologists of the time, in order to try to locate the organ of attachment and goodness.

Phrenology cast of head of Eustache known as “Belin”

Paris, circa 1840

Plaster

Rouen, Musée Flaubert et d’Histoire de la Médecine - RMM, inv. 997.3.238.G

The famous Likpo family is connected to a past that is linked to the kings of Danhomè (Dahomey, southern Benin, 1600-1894). The kings asked the arms manufacturers of Tanvé (central Benin) to copy weapons bought from Europeans in the context of the Atlantic slave trade, in order to regulate the trade. In this village, which has remained secret and is still not very accessible today, the blacksmiths proudly perpetuate the art of their ancestors. Production is now regulated by Beninese law.

LO CALZO, Nicola (1979-)

Charles and Moise Likpo, armorers,

Tanvé, Benin, 2011

FineArt pigment print - Hahnemühle Baryta paper

Private collection of the artist

LO CALZO, Nicola (1979-)

Peinture murale de Jean Jacques Dessalines, premier empereur d'Haïti (1804-1806),

Ville de Dessalines, 2013.

Séries Ayiti, Nicola Lo Calzo.

(c) Nicola Lo Calz

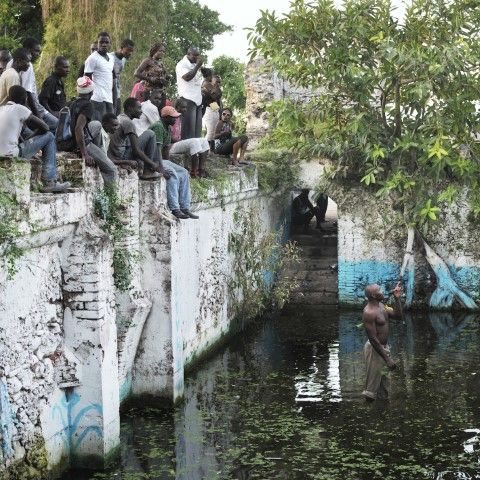

LO CALZO, Nicola (1979-)

Prière du mardi sur les ruines de l'habitation Duplaa,

connue aujourd'hui sous le nom de Lakou Lovana, au Quartier Morin, 2012.

Séries Ayiti, Nicola Lo Calzo.

(c) Nicola Lo Calzo

.jpg)

The Marquis of Choiseul-Meuse, second-in-command of Martinique, his wife, and their two children are pictured in their opulent home. The nurse beside them, dressed in white and wearing the tall West Indian ‘bamboche’, is a domestic slave. Her proximity to the family ensured her a more enviable situation than the vast majority of slaves working on the plantations. Yet, living in close proximity to her masters also made her subject to their absolute authority. There are countless examples of abuse of domestic slaves.

After Marius Pierre Le Masurier

The Choiseul-Meuse family

c. 1773 Oil on canvas, 80 x 64 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Giscard d’Estaing Collection, Accession No. 2012.5.1

Brunias’ works always portray a paradise-like image of the colonies, far removed from the realities of slavery. Here, the painter depicts the descendants of African captives who settled on the island of Saint-Vincent, in the Lesser Antilles, following the slave ship shipwrecks in around 1670. Called “Black Caribs” by the Europeans, they resisted colonization for over a century, adopting the lifestyle of the island’s original inhabitants, the “Red Caribs”.

Agostino Brunias (1730 - 1796)

Caribbeans on a Path

c. 1780 Oil on canvas, 52 x 45 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.2

This enigmatic, highly realistic portrait of a young boy differs considerably from the classic representations of the time, in which young African or Afro-descendant boys appear as servants to their mistress. The boy portrayed could have been a child taken into slavery in the West Indies from the former Dutch colonies in Brazil.

Unknown

Portrait of a Young Boy

17th or 18th century Oil on wood, 74 x 63 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.7

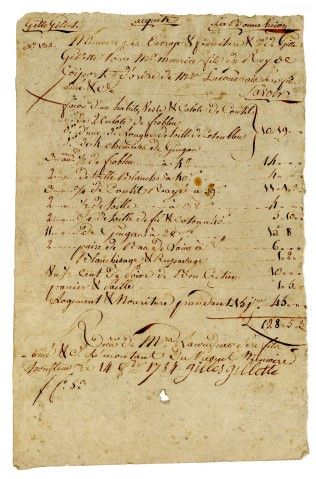

Mémoire des ouvrage & fourniture de Gilles Gillette pour Mr Maurice fils du Roy de Coiporte d'ordre de Mrs Lacoudrais Père fils aîné & Ce

Honfleur, 14 février 1784,

encre sur papier vergé, 27,5 X 17,5 cm,

musée de la Marine, Honfleur, inv. 999.0.247

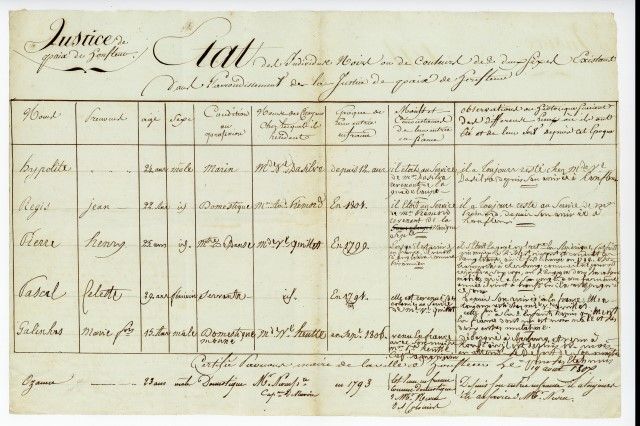

État des individus noirs ou de couleurs des deux sexes existant dans l’arrondissement de la Justice de paix de Honfleur,

19 août 1807,

encre sur papier, 25,5 X 38 cm,

Archives municipales Honfleur, cote F173

©Archives municipales de Honfleur

"This painting and its counterpart probably belong to the same series, evoking the four seasons or twelve months of the year. The abundance of flowers seems to associate this work with spring. The presence of young black slaves in decorative compositions was relatively common in the 17th century. Fewer people were enslaved in Europe than in America. In Europe, slaves were put to work at domestic chores or in minor roles in the world of theater and entertainment. They were relatively rare in 17th-century Rome, and reserved for the very wealthy. Numerous paintings reflect a certain fashion for this “exotic other”, often portrayed as a mere esthetic ornament. The work is probably the fruit of a collaboration between Franz Werner Tamm, a German artist working in Italy and specializing in floral still life, and an unknown Italian artist for the figures.

TAMM Franz Werner (Hamburg, 1658 - Vienna, 1724) (attributed to) and unknown Italian artist

Allegory of Spring

Rome, fourth quarter of the 17th century

Oil on canvas

Musée d’arts de Nantes, Cacault Collection, Acquisition, 1810, Accession No. 383

© Alain Guillard, Musée d’arts de Nantes

This painting, the counterpart to Spring, represents an allegory of autumn (or an autumnal month), as the choice of fruit and perhaps also the scene depicted on the Antique-style vase would seem to indicate. It could, in fact, be the “Abduction of Proserpine” by Pluto, which is said to be the origin of the creation of the seasons autumn and winter. This monumental decorative composition appears to be the work of two painters. The still life is said to have been painted by Christian Berentz, an artist of Nordic origin, and the figures by Italian painter Giacinto Brandi. Drawing on artists’ different specialties enabled ateliers to produce more accomplished works in a shorter space of time.

Christian BERENTZ and Giacinto BRANDI (attributed to) Hamburg, 1658 - Rome, 1722 / Gaeta, 1621 - Rome, 1691

Allegory of Autumn

Rome, fourth quarter of the 17th century

Oil on canvas

Musée d’arts de Nantes, Cacault Collection, Acquisition, 1810, Accession No. 384

© Alain Guillard, Musée d’arts de Nantes