After the exploration of the Gulf of St. Lawrence by Thomas Aubert from Dieppe in 1508, Giovanni da Verrazzano – financed by shipowners from Rouen – reached New Angoulême (later New York) in 1524, thus paving the way for the gradual colonization of the territory of New France in the 17th century. Some – such as René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle (1643-1687), once considered the discoverer of the Mississippi and founder of Louisiana – colonized the interior of the land by taking the waterways. The Normans were active in cod fishing and the beaver skin trade, under the aegis of the Compagnie de Rouen; young girls were also sent to New France to help found a colony there.

Moccasins known as “Le Couteulx” Quebec (New France),

18th century

Leather, porcupine quills

Rouen, Museum of Natural History, inv. ETHN.180705027

From the 16th century onwards, the Normans landed on the Brazilian coast to buy Brazilwood – a species that produces a red color – which gave its French name (braise) to the country, Brazil. Some of them even settled permanently to become interpreters and were nicknamed “truchements normands” (Norman middle-men), because after a few years they were no longer distinguishable from their native hosts.

Front decoration: cutting and exporting Brazilwood

Rouen, ca. 1550

Wood

Rouen, Musée des Antiquités, inv.140.1 (D)

While shipbuilding underwent a revolution at the end of the Middle Ages with the appearance of caravels adapted to long ocean voyages, navigational instruments were still based on medieval techniques. This astrolabe-quad is an example of this.

Astrolabe-quadrant and its case, known as the “Béthencourt”

Rouen? 13th-14th century

Copper and leather

Rouen, Musée des Antiquités, inv. 919

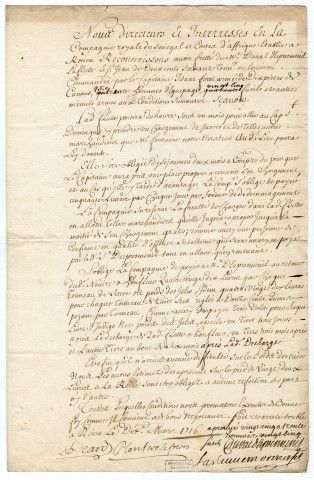

Planterose frères, Jacques Duval d’Epremesnil, Contrat d'affrètement par la Compagnie royale du Sénégal de la flûte le Saint-Jean, du Havre, appartenant à M. Duval d'Eprémesnil.

Contrat d'affrètement à la Compagnie royale du Sénégal de la flûte le Saint-Jean, du Havre, appartenant à M. Duval d'Eprémesnil / Compagnie royale du Sénégal et côtes d'Afrique.

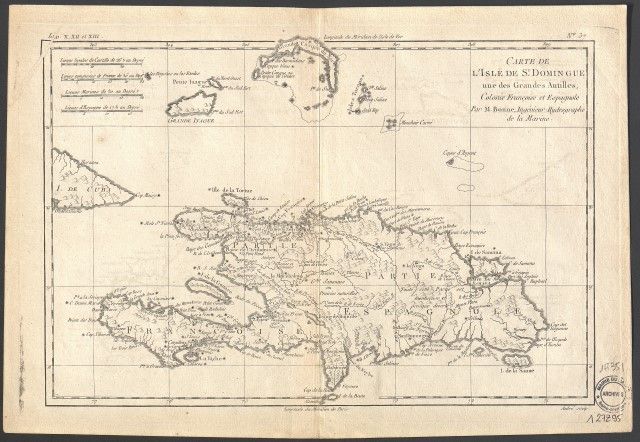

M. Bonne, ingénieur-hydrographe de la Marine,

Carte de l'Isle de Saint Domingue, une des Grandes Antilles, Colonie Françoise et Espagnole, s.l.,

XVIIIe siècle

Le Havre, Arch. mun, 1Fi351

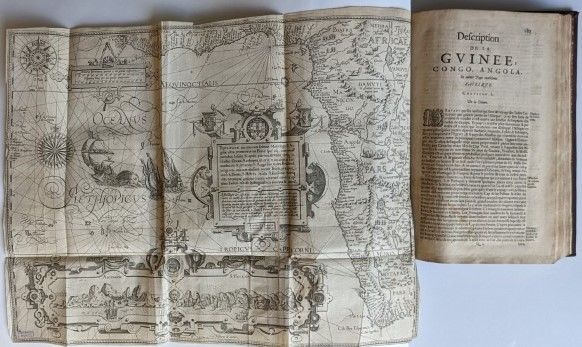

VAN LINSCHOTEN, Jan Huyghen,

Histoire de la navigation de Jean Hugues Linschot Hollandois,

Le Havre Bibl. mun., RM 761

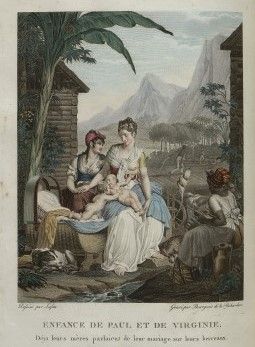

LAFFITE, Louis,

L’enfance de Paul et Virginie [Marie et Domingue]

Paris,

1806

Engraving from Bernardin de Saint Pierre's, Paul et Virginie

Le Havre, Bib. mun. Le Havre, RM 935

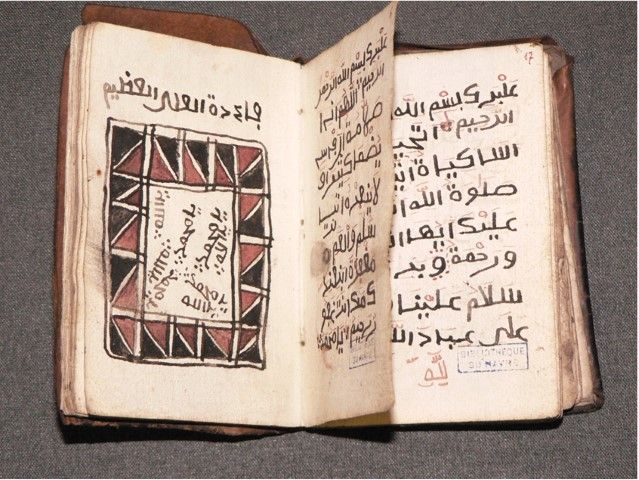

Ce manuscrit appartenait à Mak Masalidhu Muhammad, un esclave d'origine africaine mort lors d'une insurrection au Brésil. Il fut prélevé sur son corps. Malgré son échec, la révolte des esclaves musulmans à Salvador de Bahia en 1835 contribua à relancer le débat sur l'abolition de l'esclavage au Brésil. Ce manuscrit appartiendrait à l’un des insurgés.

Cartouche comprenant quatre fois l’invocation « yā Muhammad e yā-Allāh », dans Livre trouvé dans la poche d’un noir africain mort lors de l’insurrection qui éclata dans la nuit du 25 janvier 1835 à Bahia,

Bib. Le Havre Ms 556

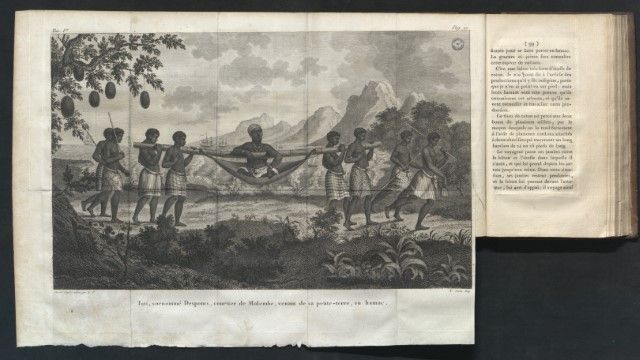

Le portrait de Tati, tiré d’un dessin « d’après nature », donne à voir un homme de pouvoir devant une rade où relâchent plusieurs navires européens. Il vient de quitter sa propriété, dite « petite-terre ». Il s’apprête à rejoindre le, le temps d’une transaction le comptoir éphémère appelé Quibanga.

G.P., del., N. COURBE,

sculp. Tati, surnommé Desponts, courtier de Malembe, venant de sa petite-terre, en hamac,

gravure extraite du Voyage a la côte occidentale d'Afrique fait dans les années 1786 et 1787 de L. Degranpré

Paris : Dentu, 1801,

Livre imprimé, 20x12cm (format fermé)

Archives départementales du Calvados, cote bh/8/12859/1-028

© AD14

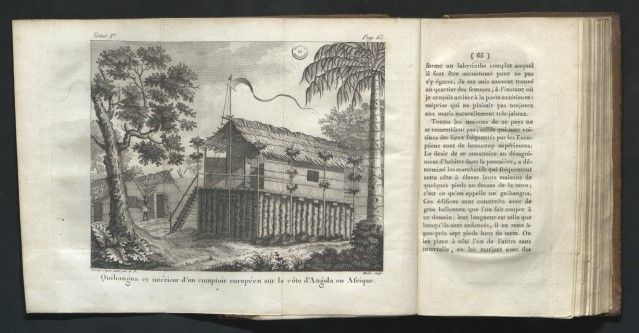

Quibangua et intérieur d'un comptoir européen sur la côte d'Angola en Afrique,

gravure extraite du Voyage a la côte occidentale d'Afrique fait dans les années 1786 et 1787

L. Degranpré Paris : Dentu, 1801

Caen, Archives départementales du Calvados bh/8/12859/1-028

© AD14

The great Western powers had been conquering the territories of the “New World” ever since its “discovery”. In this idyllic scene, the captain, white flag in hand, takes the peace pipe offered to him by the Amerindian chief. The Europeans carry a barrel and tools, while the rifle arouses curiosity among the Natives.

Unknown

Europeans Landing in America

Early 18th century Oil on canvas, 68 x 40 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.18

The great Western powers asserted their dominance over the “New World” by decimating the indigenous populations and forming vast rival colonial empires. The map’s legend indicates the territories occupied by the English, Spanish, French, and Dutch.

Father Vincenzo Maria Coronelli (1650 - 1718), improved and revised by Tillemon

Map of the Mexican Archipelago

Paris, 1688, J.B Nolin publisher Watercolor print, 51 x 67 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.43"

This map is one of the earliest representations of the island of Guadeloupe. As the cartouche states, the island was colonized by the French in 1634 (although the actual date was June 28, 1635), to the detriment of the indigenous Caribbean population, which was wiped out by as early as 1640.

Jean Boisseau (16.. - 1657?)

A Map of the Island of Guadeloupe

Pre-1643 Watercolor print, 42 x 53 cm

Bordeaux, Musée d’Aquitaine, Gift of Chatillon, Accession No. 2003.4.63

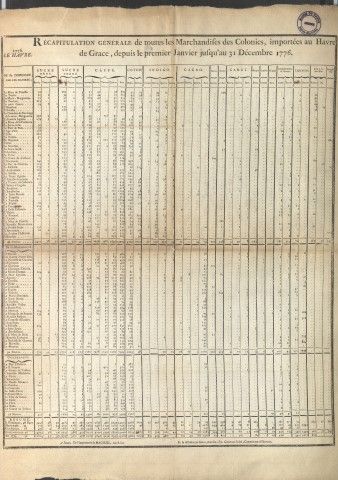

Récapitulation générale de toutes les Marchandises des Colonies, importées au Havre de Grâce, depuis le premier Janvier jusqu’au 31 Décembre 1776,

Rouen, Machuel,

Le Havre, Ch. Fr. Gentais,

1777

.jpg)

This African map was published in 1644 in Amsterdam by cartographers Henricus Hondius and Jan Jansson. Along the African coast, the map shows the main locations that would become European trading posts, roadsteads or trading sites during the second half of the 17th century. It also emphasizes Westerners’ lack of knowledge about the interior of the African continent - apart from river sites - leading to a general misrepresentation full of Amazons and gold.

Notice : © Château des ducs de Bretagne – Musée d’histoire de Nantes

HONDIUS Henricus (1597-1651), cartographer and JANSSON Jan (1588-1664) publisher Africa Nova Tabula

Circa 1644

Paper (engraving, watercolour) 40.3 x 53.7cm

Château des Ducs de Bretagne - Musée d’Histoire de Nantes, INV 927.10.1

Donated to the Salorges Museum.

Crédit photo : © Château des ducs de Bretagne – Musée d’histoire de Nantes